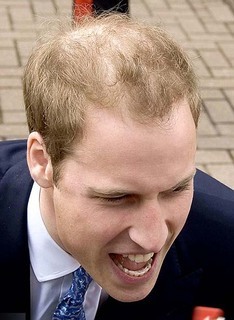

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”) T.S. Eliot – The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference. Robert Frost – The Road Not Taken

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

The lyrical repetition is emblematic of the speaker’s indecision.

The line alludes to Ecclesiastes 3:1-8: “A time to be born, and a time to die,” etc. It could also refer to the first line of Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” in which the shepherd says, “Had we but world enough and time…” and goes on to say that then he and the girl he wants could talk endlessly about whether to make love, but life is fleeting: “The grave’s a fine and private place / But none I think do there embrace.” Lonely Prufrock, though, has the time.

Another relevant passage from the same poem:

On a different topic, Eliot also uses verbs such as “slides” which add an almost snake-like quality to what the smoke is doing along the streets. Perhaps this is a biblical illusion to the serpent who tempts Adam and Eve.

1,871

Perhaps the “vegetable love” passage speaks more directly to Prufrock’s condition, his inability to decide?

5,548

I also wonder how the “vegetable love” passage is relevant. It could be, but it isn’t self-evident.

5,548

I agree that the line could refer to the opening lines of Marvell’s poem, but I think the reference is used to distinguish the vast differences between Marvell’s speaker and the situation of Eliot’s protagonist. Marvell’s speaker is using a common “carpe diem” motif to urge his lover to stop the coyness and take advantage of the time they have to consummate their love. By contrast, Eliot’s speaker is plagued by indecision and too much time, leading to a kind of anxious paralysis.